Who Was the All Knowing Chritian Man That Argued With Art Bell About People Going to Hell

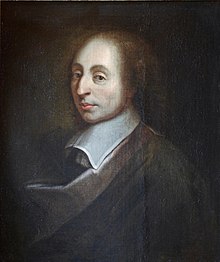

Pascal's wager is a philosophical argument presented by the seventeenth-century French philosopher, theologian, mathematician, and physicist, Blaise Pascal (1623–1662).[1] It posits that homo beings wager with their lives that God either exists or does not.

Pascal argues that a rational person should live as though God exists and seek to believe in God. If God does not be, such a person will have only a finite loss (some pleasures, luxury, etc.), whereas if God does exist, he stands to receive space gains (as represented past eternity in Heaven) and avert space losses (an eternity in Hell).[ii]

The original wager was set out in Pascal's posthumously published Pensées ("Thoughts"), an associates of previously unpublished notes.[iii] Pascal'south wager charted new territory in probability theory,[4] marked the showtime formal use of determination theory, existentialism, pragmatism, and voluntarism.[5]

The wager is commonly criticized with counterarguments such as the failure to prove the beingness of God, the argument from inconsistent revelations, and the argument from inauthentic conventionalities.

The wager [edit]

The wager uses the following logic (excerpts from Pensées, office 3, §233):

- God is, or God is non. Reason cannot make up one's mind between the two alternatives

- A Game is being played... where heads or tails volition turn up

- You must wager (it is not optional)

- Let us weigh the gain and the loss in wagering that God is. Let united states of america estimate these 2 chances. If you gain, you gain all; if y'all lose, you lose zilch

- Wager, then, without hesitation that He is. (...) At that place is here an infinity of an infinitely happy life to gain, a take a chance of gain confronting a finite number of chances of loss, and what you stake is finite. And and then our proposition is of space force when there is the finite to stake in a game where there are equal risks of gain and of loss, and the infinite to proceeds.

- But some cannot believe. They should then 'at least acquire your disability to believe...' and 'Endeavour then to convince' themselves.

Pascal asks the reader to analyze humankind's position, where our actions tin be enormously consequential, but our agreement of those consequences is flawed. While we can discern a great bargain through reason, nosotros are ultimately forced to adventure. Pascal cites a number of distinct areas of uncertainty in human being life:

| Category | Quotation(southward) |

|---|---|

| Dubiousness in all | This is what I see, and what troubles me. I look on all sides, and everywhere I see nothing but obscurity. Nature offers me nothing that is non a matter of doubt and ailment.[6] |

| Uncertainty in man's purpose | For afterward all what is man in nature? A nothing in relation to infinity, all in relation to nothing, a central bespeak betwixt zilch and all and infinitely far from agreement either.[vii] |

| Uncertainty in reason | There is zip so conformable to reason as this disavowal of reason.[eight] |

| Uncertainty in science | At that place is no doubt that natural laws exist, only once this fine reason of ours was corrupted, information technology corrupted everything.[nine] |

| Incertitude in faith | If I saw no signs of a divinity, I would set up myself in denial. If I saw everywhere the marks of a Creator, I would placidity peacefully in faith. Merely seeing too much to deny Him, and too little to clinch me, I am in a pitiful country, and I would wish a hundred times that if a god sustains nature information technology would reveal Him without ambiguity.[half dozen] Nosotros understand cipher of the works of God unless we have it as a principle that He wishes to blind some and to enlighten others.[10] |

| Doubt in skepticism | It is not sure that everything is uncertain.[xi] |

Pascal describes humanity as a finite existence trapped within an incomprehensible infinity, briefly thrust into being from non-being, with no explanation of "Why?" or "What?" or "How?" On Pascal's view, human finitude constrains our ability to attain truth reliably.

Given that reason alone cannot determine whether God exists, Pascal concludes that this question functions as a coin toss. However, even if we do not know the effect of this coin toss, we must base our actions on some expectation about the consequence. We must decide whether to live as though God exists, or whether to live as though God does not be, even though we may exist mistaken in either case.

In Pascal'south assessment, participation in this wager is non optional. Merely past existing in a state of dubiety, we are forced to choose betwixt the available courses of action for applied purposes.

Pascal's clarification of the wager [edit]

The Pensées passage on Pascal'southward wager is every bit follows:

If at that place is a God, He is infinitely incomprehensible, since, having neither parts nor limits, He has no affinity to us. We are then incapable of knowing either what He is or if He is....

..."God is, or He is non." Merely to which side shall we incline? Reason can decide naught hither. There is infinite chaos that separated the states. A game is being played at the extremity of this space distance where heads or tails will turn up. What will you wager? According to reason, you lot can do neither the ane matter nor the other; according to reason, you lot tin can defend neither of the propositions.

Do non, and then, reprove for fault those who have fabricated a choice; for y'all know nothing about it. "No, just I blame them for having fabricated, not this choice, only a option; for once more both he who chooses heads and he who chooses tails are equally at fault, they are both in the incorrect. The true form is non to wager at all."

Yes; but you must wager. It is non optional. Y'all are embarked. Which will you choose then? Let usa run into. Since y'all must choose, let united states of america see which interests you lot to the lowest degree. You have two things to lose, the true and the practiced; and two things to pale, your reason and your volition, your knowledge and your happiness; and your nature has ii things to shun, error and misery. Your reason is no more shocked in choosing one rather than the other since you must of necessity choose. This is ane signal settled. Simply your happiness? Let us weigh the gain and the loss in wagering that God is. Let united states approximate these two chances. If you lot gain, you lot gain all; if y'all lose, you lose nothing. Wager, and so, without hesitation that He is.

"That is very fine. Yes, I must wager; only I may mayhap wager too much." Let us see. Since there is an equal risk of gain and of loss, if you had only to proceeds ii lives, instead of one, you lot might still wager. But if there were 3 lives to proceeds, y'all would have to play (since you are under the necessity of playing), and you would exist imprudent, when yous are forced to play, non to change your life to gain three at a game where there is an equal risk of loss and gain. But there is an eternity of life and happiness. And this being and so, if there were an infinity of chances, of which one only would exist for you, you would nonetheless be right in wagering one to win ii, and you would human activity stupidly, being obliged to play, by refusing to stake one life against three at a game in which out of an infinity of chances there is ane for you if there were an infinity of an infinitely happy life to gain. But there is hither an infinity of an infinitely happy life to proceeds, a chance of gain against a finite number of chances of loss, and what yous pale is finite.[12]

Pascal begins by painting a situation where both the existence and non-existence of God are incommunicable to show by human reason. And so, supposing that reason cannot determine the truth betwixt the two options, one must "wager" by weighing the possible consequences. Pascal's assumption is that, when information technology comes to making the conclusion, no one tin refuse to participate; withholding assent is impossible because we are already "embarked", effectively living out the choice.

We only accept two things to stake, our "reason" and our "happiness". Pascal considers that if there is "equal risk of loss and gain" (i.e. a coin toss), then human being reason is powerless to address the question of whether God exists. That being the case, then human reason can but decide the question co-ordinate to possible resulting happiness of the decision, weighing the gain and loss in assertive that God exists and as well in believing that God does not be.

He points out that if a wager were between the equal chance of gaining ii lifetimes of happiness and gaining nothing, and so a person would be a fool to bet on the latter. The same would go if it were three lifetimes of happiness versus zilch. He then argues that it is merely unconscionable by comparison to betting against an eternal life of happiness for the possibility of gaining nothing. The wise decision is to wager that God exists, since "If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nil", meaning one can gain eternal life if God exists, just if not, one volition exist no worse off in death than if one had non believed. On the other hand, if you bet confronting God, win or lose, yous either gain nothing or lose everything. You are either unavoidably annihilated (in which case, nothing matters 1 way or the other) or miss the opportunity of eternal happiness. In note 194, speaking well-nigh those who live apathetically betting confronting God, he sums upwards past remarking, "It is to the glory of religion to have for enemies men and then unreasonable..."

Inability to believe [edit]

Pascal addressed the difficulty that 'reason' and 'rationality' pose to 18-carat belief by proposing that "acting equally if [1] believed" could "cure [one] of unbelief":

Simply at least learn your inability to believe, since reason brings you to this, and yet you cannot believe. Attempt then to convince yourself, not by increase of proofs of God, but by the abatement of your passions. You would like to achieve religion, and do not know the way; you would like to cure yourself of unbelief and inquire the remedy for it. Larn of those who have been jump like you, and who now pale all their possessions. These are people who know the way which you would follow, and who are cured of an sick of which you would be cured. Follow the way past which they began; by interim as if they believed, taking the holy h2o, having masses said, etc. Even this volition naturally make y'all believe, and deaden your acuteness.[13]

Analysis with decision theory [edit]

The possibilities defined by Pascal's wager tin exist thought of as a decision under uncertainty with the values of the following conclusion matrix.

| God exists (G) | God does non be (¬G) | |

|---|---|---|

| Belief (B) | +∞ (infinite gain) | −c (finite loss) |

| Atheism (¬B) | −∞ (space loss) | +c (finite gain) |

Given these values, the pick of living equally if God exists (B) dominates the selection of living as if God does not be (¬B), every bit long equally 1 assumes a positive probability that God exists. In other words, the expected value gained by choosing B is greater than or equal to that of choosing ¬B.

In fact, according to decision theory, the only value that matters in the higher up matrix is the +∞ (infinitely positive). Any matrix of the following type (where f1, fii, and f3 are all negative or finite positive numbers) results in (B) every bit beingness the only rational conclusion.[v]

| God exists (Yard) | God does not exist (¬G) | |

|---|---|---|

| Belief (B) | +∞ | fane |

| Disbelief (¬B) | ftwo | f3 |

Misunderstanding of the wager [edit]

Pascal's intent was not to provide an argument to convince atheists to believe, only (a) to show the fallacy of attempting to utilize logical arguments to prove or disprove God, and (b) to persuade atheists to sinlessness, as an aid to attaining faith ("it is this which will lessen the passions, which are your stumbling-blocks"). As Laurent Thirouin writes (note that the numbering of the items in the Pensees is not standardized; Thirouin'due south 418 is this commodity's 233):

The celebrity of fragment 418 has been established at the price of mutilation. By titling this text "the wager", readers take been fixated only on one part of Pascal's reasoning. It doesn't conclude with a QED at the end of the mathematical part. The unbeliever who had provoked this long assay to counter his previous objection ("Maybe I bet besides much") is still non ready to bring together the apologist on the side of religion. He put forward two new objections, undermining the foundations of the wager: the impossibility to know, and the obligation of playing.[fourteen]

To exist put at the beginning of Pascal'south planned book, the wager was meant to evidence that logical reasoning cannot support religion or lack thereof,

We have to accept reality and have the reaction of the libertine when he rejects arguments he is unable to counter. The determination is axiomatic: if men believe or turn down to believe, information technology is not how some believers sometimes say and most unbelievers claim because their ain reason justifies the position they take adopted. Belief in God doesn't depend upon rational prove, no matter which position.[xv]

Pascal's intended book was precisely to discover other ways to establish the value of organized religion, an amends for the Christian religion.

Criticism [edit]

Criticism of Pascal's wager began in his own day, and came from atheists, who questioned the "benefits" of a deity whose "realm" is across reason and the religiously orthodox, who primarily took outcome with the wager's deistic and agnostic linguistic communication. It is criticized for not proving God'due south being, the encouragement of faux belief, and the problem of which religion and which God should be worshipped.[4] [xvi]

Laplace [edit]

The probabilist mathematician Pierre Simon de Laplace ridiculed the use of probability in theology. Even following Pascal'due south reasoning, it is not worth making a bet, for the hope of profit – equal to the production of the value of the testimonies (infinitely small) and the value of the happiness they promise (which is meaning but finite) – must necessarily be infinitely pocket-sized.[17]

Failure to evidence the existence of God [edit]

Voltaire (another prominent French writer of the Enlightenment), a generation afterward Pascal, rejected the idea that the wager was "proof of God" every bit "indecent and childish", calculation, "the interest I have to believe a affair is no proof that such a matter exists".[18] Pascal, still, did not advance the wager as a proof of God's beingness just rather as a necessary pragmatic decision which is "impossible to avoid" for any living person.[19] He argued that abstaining from making a wager is not an option and that "reason is incapable of divining the truth"; thus, a conclusion of whether to believe in the existence of God must be made by "because the consequences of each possibility".

Voltaire's critique concerns non the nature of the Pascalian wager as proof of God's existence, merely the contention that the very conventionalities Pascal tried to promote is non convincing. Voltaire hints at the fact that Pascal, as a Jansenist, believed that merely a small, and already predestined, portion of humanity would somewhen be saved by God.

Voltaire explained that no thing how far someone is tempted with rewards to believe in Christian conservancy, the effect will be at best a faint belief.[xx] Pascal, in his Pensées, agrees with this, not stating that people can cull to believe (and therefore make a safe wager), but rather that some cannot believe.

As Étienne Souriau explained, in order to have Pascal's statement, the bettor needs to exist certain that God seriously intends to honour the bet; he says that the wager assumes that God also accepts the bet, which is not proved; Pascal's bettor is hither like the fool who seeing a leaf floating on a river's waters and quivering at some signal, for a few seconds, between the two sides of a rock, says: "I bet a million with Rothschild that it takes finally the left path." And, finer, the leaf passed on the left side of the rock, but unfortunately for the fool Rothschild never said "I [volition have that] bet".[21]

Statement from inconsistent revelations [edit]

Since there take been many religions throughout history, and therefore many conceptions of God (or gods), some assert that all of them demand to be factored into the wager, in an argumentation known every bit the argument from inconsistent revelations. This, its proponents debate, would lead to a high probability of believing in "the wrong god", which, they claim, eliminates the mathematical advantage Pascal claimed with his wager.[iv] Denis Diderot, a gimmicky of Voltaire, concisely expressed this opinion when asked about the wager, proverb "an Imam could reason the aforementioned way".[22] J. L. Mackie notes that "the church within which alone salvation is to be institute is not necessarily the Church of Rome, just perhaps that of the Anabaptists or the Mormons or the Muslim Sunnis or the worshipers of Kali or of Odin."[23] As just stated, the counterargument is flawed, since well-nigh religions do not say that belief in their detail god (Kali or Odin, for example) is necessary for bliss, only that flaw is easily remediable past using advisable religions (Anabaptists vs. Roman Catholics).

Another version of this objection argues that for every religion that promulgates rules, in that location exists another religion that has rules of the opposite kind, e.m., Christianity requires the adherent to worship Jesus as God, merely Judaism requires the adherent not to worship Jesus as God. If a certain action leads i closer to salvation in the former religion, information technology leads 1 further away from information technology in the latter. Therefore, the expected value of following a certain religion could be negative. Or, i could besides argue that there are an infinite number of mutually exclusive religions (which is a subset of the gear up of all possible religions), and that the probability of any one of them beingness truthful is zero; therefore, the expected value of following a certain faith is nada.

Pascal considers this blazon of objection briefly in the notes compiled into the Pensées, and dismisses it as obviously wrong and disingenuous:[24]

What say [the unbelievers] and so? "Do we not see," say they, "that the brutes alive and die similar men, and Turks like Christians? They accept their ceremonies, their prophets, their doctors, their saints, their monks, like united states," etc. If you care but niggling to know the truth, that is enough to exit you in repose. But if you desire with all your centre to know it, it is non enough; await at it in detail. That would exist sufficient for a question in philosophy; but non here, where everything is at stake. And still, subsequently a superficial reflection of this kind, we go to amuse ourselves, etc. Let us inquire of this same religion whether it does not requite a reason for this obscurity; perhaps information technology will teach it to us.[25]

This brusk but densely packed passage, which alludes to numerous themes discussed elsewhere in the Pensées, has given rise to many pages of scholarly analysis.

Pascal says that the skepticism of unbelievers who rest content with the many-religions objection has seduced them into a fatal "repose". If they were really bent on knowing the truth, they would be persuaded to examine "in particular" whether Christianity is like whatever other religion, only they just cannot be bothered.[26] Their objection might be sufficient were the subject concerned merely some "question in philosophy", but not "hither, where everything is at pale". In "a matter where they themselves, their eternity, their all are concerned",[25] they tin can manage no better than "a superficial reflection" ("une reflexion légère") and, thinking they have scored a point past request a leading question, they become off to amuse themselves.[27]

As Pascal scholars find, Pascal regarded the many-religions objection as a rhetorical ploy, a "trap"[28] that he had no intention of falling into. If, withal, any who raised information technology were sincere, they would want to examine the matter "in detail". In that case, they could get some pointers past turning to his affiliate on "other religions".

David Wetsel notes that Pascal's treatment of the pagan religions is brisk: "As far as Pascal is concerned, the demise of the pagan religions of artifact speaks for itself. Those pagan religions which still exist in the New Globe, in Republic of india, and in Africa are not even worth a 2nd glance. They are plain the piece of work of superstition and ignorance and have nada in them which might involvement 'les gens habiles' ('clever men')[29]".[thirty] Islam warrants more attending, being distinguished from paganism (which for Pascal presumably includes all the other not-Christian religions) by its claim to be a revealed religion. Nevertheless, Pascal concludes that the faith founded past Mohammed tin on several counts be shown to exist devoid of divine authority, and that therefore, as a path to the cognition of God, information technology is as much a dead end as paganism."[31] Judaism, in view of its close links to Christianity, he deals with elsewhere.[32]

The many-religions objection is taken more than seriously by some later apologists of the wager, who contend that of the rival options only those application space happiness affect the wager'southward dominance. In the opinion of these apologists "finite, semi-blissful promises such as Kali's or Odin's" therefore drop out of consideration.[five] Also, the infinite bliss that the rival conception of God offers has to be mutually exclusive. If Christ'southward hope of bliss can be attained concurrently with Jehovah's and Allah's (all 3 existence identified equally the God of Abraham), at that place is no disharmonize in the conclusion matrix in the case where the cost of assertive in the wrong conception of God is neutral (limbo/purgatory/spiritual death), although this would be countered with an infinite cost in the example where not believing in the correct conception of God results in penalisation (hell).[33]

Ecumenical interpretations of the wager[34] argues that it could even be suggested that believing in a generic God, or a god by the wrong name, is adequate so long as that formulation of God has similar essential characteristics of the conception of God considered in Pascal's wager (perhaps the God of Aristotle). Proponents of this line of reasoning suggest that either all of the conceptions of God or gods throughout history truly boil downwardly to simply a small set of "genuine options", or that if Pascal'due south wager can but bring a person to believe in "generic theism", it has done its job.[33] The wager fails every bit an argument for believing exclusively in ecumenical religions, or believing at all in universalist religions that practice non believe only their adherents reach eternal bliss.[ citation needed ]

Pascal argues implicitly for the uniqueness of Christianity in the wager itself, writing: "If in that location is a God, He is infinitely incomprehensible...Who then tin can blame the Christians for non beingness able to requite reasons for their beliefs, professing as they do a faith which they cannot explain past reason?"[35]

Argument from inauthentic conventionalities [edit]

Some critics argue that Pascal'south wager, for those who cannot believe, suggests feigning conventionalities to gain eternal reward. Richard Dawkins argues that this would be quack and immoral and that, in add-on to this, it is absurd to call up that God, being just and omniscient, would not run across through this deceptive strategy on the office of the "believer", thus nullifying the benefits of the wager.[xvi]

Since these criticisms are concerned not with the validity of the wager itself, but with its possible aftermath—namely that a person who has been convinced of the overwhelming odds in favor of belief might however find himself unable to sincerely believe—they are tangential to the thrust of the wager. What such critics are objecting to is Pascal's subsequent advice to an unbeliever who, having concluded that the only rational fashion to wager is in favor of God'south existence, points out, reasonably enough, that this past no ways makes him a believer. This hypothetical unbeliever complains, "I am so fabricated that I cannot believe. What would you lot have me exercise?"[36] Pascal, far from suggesting that God can be deceived past outward show, says that God does not regard it at all: "God looks merely at what is inward."[37] For a person who is already convinced of the odds of the wager just cannot seem to put his eye into the belief, he offers applied advice.

Explicitly addressing the question of disability to believe, Pascal argues that if the wager is valid, the inability to believe is irrational, and therefore must be caused by feelings: "your inability to believe, because reason compels you lot to [believe] and yet you cannot, [comes] from your passions." This inability, therefore, can be overcome by diminishing these irrational sentiments: "Learn from those who were jump like yous. . . . Follow the way by which they began; by acting every bit if they believed, taking the holy water, having masses said, etc. Even this will naturally make you believe, and deaden your acuteness.—'Simply this is what I am afraid of.'—And why? What have y'all to lose?"[38]

An uncontroversial doctrine in both Roman Catholic and Protestant theology is that mere conventionalities in God is insufficient to attain salvation, the standard cite beingness James 2:xix: "Thou believest that in that location is one God; thou doest well: the devils also believe, and tremble." Conservancy requires "religion" not just in the sense of belief, but of trust and obedience. Pascal and his sister, a nun, were amongst the leaders of Roman Catholicism's Jansenist school of thought whose doctrine of salvation was close to Protestantism in emphasizing organized religion over works. Both Jansenists and Protestants followed St. Augustine in this emphasis (Martin Luther belonged to the Augustinian Order of monks). Augustine wrote

And so our faith has to be distinguished from the faith of the demons. Our organized religion, yous run into, purifies the heart, their faith makes them guilty. They human action wickedly, and so they say to the Lord, "What take you to do with us?" When you lot hear the demons maxim this, practice you imagine they don't recognize him? "We know who you are," they say. "You are the Son of God" (Lk four:34). Peter says this and he is praised for it; 14 the demon says it, and is condemned. Why's that, if not because the words may exist the same, but the heart is very different? So let us distinguish our faith, and see that believing is not plenty. That's not the sort of organized religion that purifies the heart.[39]

Since Pascal's position was that "saving" belief in God required more than logical assent, accepting the wager could only be a first footstep. Hence his communication on what steps i could have to arrive at belief.

Some other critics[ who? ] have objected to Pascal's wager on the grounds that he wrongly assumes what type of epistemic character God would likely value in his rational creatures if he existed.

Variations and other wager arguments [edit]

- The sophist Protagoras had an agnostic position regarding the gods, merely he nevertheless connected to worship the gods. This could be considered as an early version of the Wager.[40]

- In the famous tragedy of Euripides Bacchae, Kadmos states an early on version of Pascal's wager. It is noteworthy that at the finish of the tragedy Dionysos, the god to whom Kadmos referred, appears and punishes him for thinking in this way. Euripides, quite clearly, considered and dismissed the wager in this tragedy.[41]

- The stoic philosopher and Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius expressed a similar sentiment in the second book of Meditations, maxim "Since it is possible that thou mayest depart from life this very moment, regulate every deed and thought accordingly. But to get away from amidst men, if at that place are gods, is not a matter to exist afraid of, for the gods will not involve thee in evil; but if indeed they practise non exist, or if they accept no business organization about human being affairs, what is information technology to me to live in a universe devoid of gods or devoid of Providence?"[42]

- In the Sanskrit classic Sārasamuccaya, Vararuci makes a similar argument to Pascal's wager.[43]

- Muslim Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq is recorded to accept postulated variations of the wager on several occasions in dissimilar forms, including his famed 'Tradition of the Myrobalan Fruit.'[44] In the Shi'i hadith book al-Kafi, al-Sadiq declares to an atheist "If what y'all say is correct – and information technology is non – then we will both succeed. Simply if what I say is correct – and it is – then I will succeed, and you will exist destroyed."[45]

- An instantiation of this argument, inside the Islamic kalam tradition, was discussed by Imam al-Haramayn al-Juwayni (d. 478/1085) in his Kitab al-irshad ila-qawati al-adilla fi usul al-i'tiqad, or A Guide to the Conclusive Proofs for the Principles of Conventionalities.[46]

- The Christian apologist Arnobius of Sicca (d. 330) stated an early version of the argument in his book Against the Pagans, arguing "is it not more rational, of two things uncertain and hanging in doubtful suspense, rather to believe that which carries with it some hopes, than that which brings none at all?"[47] [48]

- A close parallel but before Pascal's time occurred in the Jesuit Antoine Sirmond'south On the Immortality of the Soul (1635), which explicitly compared the choice of religion to playing dice and argued "However long and happy the space of this life may be, while always you place it in the other pan of the rest confronting a blessed and flourishing eternity, surely information technology will seem to you ... that the pan will ascension on high."[47] : 30

- The Atheist's Wager, popularised by the philosopher Michael Martin and published in his 1990 book Disbelief: A Philosophical Justification, is an atheistic wager argument in response to Pascal'due south wager.[49]

- A 2008 philosophy book, How to Brand Skilful Decisions and Be Right All the Fourth dimension, presents a secular revision of Pascal'southward wager: "What does it hurt to pursue value and virtue? If there is value, then we have everything to gain, but if at that place is none, then we haven't lost anything.... Thus, nosotros should seek value."[50]

- Roko'southward basilisk is a hypothetical future superintelligence that punishes everyone who failed to help bring information technology into existence.[51]

- In a 2014 article, philosopher Justin P. McBrayer argued nosotros ought to remain agnostic well-nigh the existence of God simply nonetheless believe because of the practiced that comes in the present life from believing in God. "The gist of the renewed wager is that theists do better than non-theists regardless of whether or not God exists."[52]

Climate change [edit]

Since at least 1992, some scholars accept analogized Pascal's wager to decisions virtually catastrophic climatic change.[53] Two differences from Pascal's wager are posited regarding climate alter: start, climatic change is more likely than Pascal'due south God to exist, equally there is scientific evidence for one just not the other.[54] Secondly, the calculated punishment for unchecked climate ending would be large, merely is not generally considered to be infinite.[55] Magnate Warren Buffett has written that climate change "bears a similarity to Pascal's Wager on the Beingness of God. Pascal, it may be recalled, argued that if at that place were merely a tiny probability that God truly existed, it made sense to behave as if He did because the rewards could be infinite whereas the lack of belief risked eternal misery. Likewise, if there is just a 1% chance the planet is heading toward a truly major disaster and delay means passing a indicate of no return, inaction now is foolhardy."[56] [57]

Run into likewise [edit]

- A Confession

- Appeal to consequences

- Argumentum advert baculum

- Atheist's Wager

- Christian existential apologetics

- Ecclesiastes

- Evil God Challenge

- Lewis'southward trilemma

- Four Assurances

- Buddhist wager argument for rebirth

- Pascal's mugging

- Pensées

Notes [edit]

- ^ Connor, James A. (2006). Pascal's wager : the human who played dice with God . San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco. pp. 180–i. ISBN9780060766917.

- ^ "Blaise Pascal", Columbia History of Western Philosophy, page 353.

- ^ Clarke, Desmond (June 22, 2015). "Blaise Pascal". In Zalta, Edward Northward. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2015 ed.).

- ^ a b c Podgorski, Daniel (Dec eighteen, 2015). "A Logical Infinite: The Constrained Probabilistic Definitions of Chance and Infinity in Blaise Pascal's Famous Wager". The Gemsbok . Retrieved Apr 21, 2016.

- ^ a b c Hájek, Alan (Nov 6, 2012). "Pascal's Wager". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ^ a b Pensée #229

- ^ Pensée #72

- ^ Pensée #272

- ^ Pensée #294

- ^ Pensée #565

- ^ Pensée #387

- ^ Pensées, Section III, 233.

- ^ Pensées Section III notation 233, Translation by West. F. Trotter

- ^ Laurent Thiroin, Le hasard et les règles, le modèle du jeu dans la pensée de Pascal, Vrin, Paris 1991, p.170

- ^ Laurent Thiroin, Le hasard et les règles, le modèle du jeu dans la pensée de Pascal, Vrin, Paris 1991, p.176

- ^ a b Dawkins, Richard (May 21, 2007). "Chapter 3: Arguments for God's existence". The God Delusion. Black Swan. pp. 130–132. ISBN9780552773317.

- ^ Jacques Attali (2004), Pascal, Warszawa, p. 368

- ^ Voltaire (1728). "Remarques (Premiéres) sur les Pensées de Pascal". Oeuvres Complétes de Voltaire. Mélanges I (in French). Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved Apr 24, 2016.

- ^ Durant, Will and Ariel (1965). The Historic period of Voltaire . pp. 370.

- ^ Vous me promettez l'empire du monde si je crois que vous avez raison: je souhaite alors, de tout mon coeur, que vous ayez raison; mais jusqu'à ce que vous me 50'ayez prouvé, je ne puis vous croire. […] J'ai intérêt, sans doute, qu'il y ait un Dieu; mais si dans votre système Dieu north'est venu que cascade si peu de personnes; si le petit nombre des élus est si effrayant; si je ne puis rien du tout par moi-même, dites-moi, je vous prie, quel intérêt j'ai à vous croire? North'ai-je pas un intérêt visible à être persuadé du contraire? De quel front osez-vous me montrer un bonheur infini, auquel d'un million d'hommes un seul à peine a droit d'aspirer?

- ^ À vrai dire le célèbre pari de Pascal, ou plutôt le pari que Pascal propose au libertin due north'est pas une option désintéressée mais united nations pari de joueur. Si le libertin joue «croix», parie que Dieu existe, il gagne (si Dieu existe) la vie éternelle et la béatitude infinie, et risque seulement de perdre les misérables plaisirs de sa vie actuelle. Cette mise ne compte pas au regard du gain possible qui est infini. Seulement, l'statement suppose que Dieu accepte le pari, que Dieu dit «je tiens». Sans quoi, nous dit Souriau, le libertin « est comme ce fou : il voit une feuille au fil de l'eau, hésiter entre deux côtés d'un caillou. Il dit : «je parie un million avec Rothschild qu'elle passera à droite». La feuille passe à droite et le fou dit : «j'ai gagné united nations million». Où est sa folie? Ce n'est pas que le 1000000 n'existe pas, c'est que Rothschild due north'a pas dit : «je tiens». ». (Cf. l'admirable analyse du pari de Pascal in Souriau, 50'ombre de Dieu, p. 47 sq.) – La Philosophie, Tome 2 (La Connaissance), Denis Huisman, André Vergez, Marabout 1994, pp. 462–63

- ^ Diderot, Denis (1875–77) [1746]. J. Assézar (ed.). Pensées philosophiques, LIX, Book ane (in French). p. 167.

- ^ Mackie, J. L. (1982). The Miracle of Theism, Oxford, pg. 203

- ^ Wetsel, David (1994). Pascal and Disbelief: Catechesis and Conversion in the Pensées. Washington, D. C.: The Catholic University of America Press, p. 117. ISBN 0-8132-1328-2

- ^ a b Pensée #226

- ^ Wetsel, Pascal and Disbelief, p. 370.

- ^ Wetsel, Pascal and Disbelief, p. 238.

- ^ Wetsel, Pascal and Disbelief, pp. 118 (quotation from Jean Mesnard), 236.

- ^ Pensée #251

- ^ Wetsel, Pascal and Disbelief, p. 181.

- ^ Wetsel, Pascal and Disbelief, p. 182.

- ^ Wetsel, Pascal and Disbelief, p. 180.

- ^ a b Saka, Paul. "Pascal'southward Wager about God". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ^ For instance: Jeff Hashemite kingdom of jordan, Gambling on God: Essays on Pascal's Wager, 1994, Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ Pascal, Blaise (1932). "Pascal's Wager: 343 [6-233]" (PDF). Pensées. Translated by Warrington, John. Lowest'due south Library No. 874. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 13, 2019 – via ucla.edu.

- ^ Pensée #233

- ^ Pensée #904

- ^ Pensée #233. Gérard Ferreyrolles, ed. Paris: Librairie Générale Française, 2000.

- ^ DTK, "A Person is Justified by Works - (James 2:14-26)", Puritanboard.com, https://world wide web.puritanboard.com/threads/a-person-is-justified-past-works-james-two-xiv-26.13531/, (May 2, 2006) viewed Jan 21, 2021, citing John E. Rotelle, O.S.A., ed.,WSA, Sermons, Function iii, Vol. 3, trans. Edmund Hill, O.P., "Sermon 53.xi" (Brooklyn: New City Press, 1991), p. 71. DTK collects several other Augustine quotes on the topic, with similarly precise citations.

- ^ Boyarin, Daniel (2009). Socrates & the fat rabbis . University of Chicago Press. p. 48. ISBN978-0-226-06916-6.

- ^ Weaver, John B. (2004). Plots of epiphany: prison-escape in Acts of the Apostles. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 453–454, 595. ISBN978-3-11-018266-viii.

- ^ "The Internet Classics Annal | The Meditations by Marcus Aurelius". classics.mit.edu . Retrieved 2019-01-27 .

- ^ Ostler, Nicholas (2005). Empires of the Word. HarperCollins.

- ^ "The Hadith". Tradition of the Myrobalan Fruit. Al-Islam.org. 2017.

- ^ al-Kulainī, M. (1982). al- Kāfī. Tehran: Grouping of Muslim Brothers.

- ^ al-Juwayni A Guide to Conclusive Proofs for the Principles of Belief, 6

- ^ a b Franklin, James (2001). "Pascal'southward wager and the origins of conclusion theory: decision-making by real conclusion-makers" (PDF). In Bartha, P.; Pasternack, Fifty. (eds.). Classic Philosophical Arguments: Pascal's Wager. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing. pp. 27–44. ISBN978-1107181434.

- ^ Aleksandrovich Florenskiĭ, Pavel (1997). The colonnade and footing of the truth (1914). Princeton University Press. p. 37. ISBN0-691-03243-2.

- ^ Martin, Michael (1990). "ix". Atheism: A Philosophical Justification. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN9780877226420.

- ^ 24 and Philosophy (2014)

- ^ Paul-Choudhury, Sumit. "Tomorrow'due south Gods: What is the hereafter of faith?". BBC . Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ McBrayer, Justin P. (23 September 2014). "The Wager Renewed: Believing in God is Healthy" (PDF). Science, Religion and Culture. 1 (3): 130–140. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ Orr, D. W. (1992). "Pascals wager and economics in a hotter time". Ecological Economics. 6 (i): ane–six. doi:10.1016/0921-8009(92)90035-q.

- ^ Nathan, Green (July 3, 2012). "How to bet on climate change". The Guardian . Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ van der Ploeg, Frederick; Rezai, Armon (January 2019). "The agnostic's response to climate deniers: Price carbon!". European Economic Review. pp. 70–84. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2018.08.010.

- ^ Buffet, W. (Feb 27, 2016). "To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway, Inc" (PDF). Berkshire Hathaway, Inc. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ Oyedele, Akin (2019). "Warren Buffett on global warming: 'This result bears a similarity to Pascal's Wager on the Existence of God.'". Concern Insider . Retrieved 25 February 2020.

References [edit]

- al-Juwayni, Imam al-Haramayn (2000). Walker, Dr. Paul East. (ed.). A Guide to Conclusive Proofs for the Principles of Belief. Reading, Great britain: Garnet Publishing. pp. six–7. ISBNone-85964-157-1.

- Armour, Leslie. Infini Rien: Pascal's Wager and the Human Paradox. The Journal of the History of Philosophy Monograph Series. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1993.

- Cargile, James. "Pascal's Wager". Contemporary Perspectives on Religious Epistemology. R. Douglas Geivett and Brendan Sweetman, eds. Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Dawkins, Richard. "Pascal's Wager". The God Mirage. Blackness Swan, 2007 (ISBN 978-0-552-77429-i).

- Holowecky, Elizabeth. "Taxes and God". KPMG Press, 2008. (Telephone interview)

- Jordan, Jeff, ed. Gambling on God. Lanham Medico: Rowman & Littlefield, 1994. (A drove of recent articles on the Wager with a bibliography.)

- Jordan, Jeff. Pascal'south Wager: Pragmatic Arguments and Conventionalities in God. Oxford University Printing, 2007.

- Lycan, William 1000. and George Due north. Schlesinger, "Y'all Bet Your Life: Pascal'southward Wager Defended". Gimmicky Perspectives on Religious Epistemology. R. Douglas Geivett and Brendan Sweetman, eds. Oxford Academy Press, 1992.

- Martin, Michael. Atheism. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990. (Pp. 229–238 presents the statement about a god who punishes believers.)

- Morris, Thomas Five. "Pascalian Wagering". Contemporary Perspectives on Religious Epistemology. R. Douglas Geivett and Brendan Sweetman, eds. Oxford University Printing, 1992.

- Rescher, Nicholas. Pascal's Wager: A Study of Practical Reasoning in Philosophical Theology. University of Notre Dame Printing, 1985. (The outset book-length treatment of the Wager in English.)

- Whyte, Jamie. Crimes against Logic. McGraw-Hill, 2004. (Section with argument about Wager)

External links [edit]

- Pascal'due south Pensees Part III — "The Necessity of the Wager" (Trotter translation), at Classical Library (Wager found at #233)

- Section III of Blaise Pascal's Pensées, Translated by W. F. Trotter (with foreword past T. Due south. Eliot), at Project Gutenburg (Wager institute at #233)

- Pascal's Wager in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Pascal'south Wager in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Pascal'southward Wager: Pragmatic Arguments and Belief in God (2006) past Jeff Hashemite kingdom of jordan, University of Delaware, 2006

- Ambivalence, Pessimism, and Rational Religious Choice (2010) by Tigran Melkonyan and Mark Pingle, Theory and Determination, 2010, Volume 69, Number 3, Pages 417–438

- The Rejection of Pascal'southward Wager by Paul Tobin

- Pascal's Mugging by Nick Bostrom

- Theistic Conventionalities and Religious Doubtfulness by Jeffrey Jordan

abrahamshookeplise79.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pascal%27s_wager

0 Response to "Who Was the All Knowing Chritian Man That Argued With Art Bell About People Going to Hell"

Post a Comment