Guy Buys a Lottery Ticket and Shows How We What Do You Want and How We Wanted and Then Wins Again

It was the biggest lottery scam in American history.

The video was grainy, just it showed plenty to maybe crack open the biggest lottery scam in American history. A heavyset man walks into a QuikTrip convenience shop just off Interstate eighty in Des Moines, Iowa, two days before Christmas 2010. The hood of his sweatshirt is pulled over his caput, obscuring his face. He grabs a fountain drink and two hot dogs.

"Hello!" the cashier says brightly.

Head downward, the human replies in a low-pitched drawl: "Hell-ooooh."

They exchange a few more words. The man pulls ii pieces of newspaper from his pocket. The cashier runs them through the lottery terminal and then easily over some change. Once exterior, the homo pulls off his hood, gets into his SUV, and drives away.

The pieces of paper were play slips for Hot Lotto, a lottery game that was bachelor in 14 states and Washington, DC. A player (or the game's computer) picked v numbers and and so a sixth, known as the Hot Ball. Players who got all six numbers correct won a jackpot that varied according to how many tickets were sold. At the time of the video, the jackpot was approaching $10 million. The stated odds of winning it were ane in x,939,383.

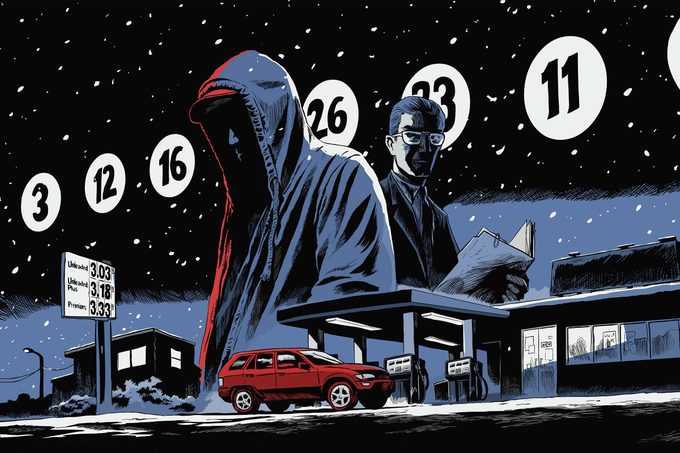

Vi days later, on December 29, the Hot Lotto numbers were selected: three, 12, 16, 26, 33, 11. The side by side day, the Iowa Lottery announced that a QuikTrip in Des Moines had sold the winning ticket. But no one came forwards to claim the now $sixteen.5 million jackpot.

After a month passed, the Iowa Lottery held a news conference to note that the money was still united nationscollected. The lottery issued another public reminder 3 months later on the winning numbers were appear, then another at half dozen months and again at nine months, each time warning that winners had one twelvemonth to claim their money.

In November 2011, a man named Philip Johnston, a Canadian attorney, called in with the right serial number from the winning ticket. Only when asked what he'd been wearing when he bought it, his description of a sports glaze and grey flannel dress pants did not match the QuikTrip video. Then, in a subsequent call, the man admitted he had "fibbed"; he said he was helping a client merits the ticket so the customer wouldn't be identified.

This was against the Iowa Lottery rules, which require identities of winners to be public. Lottery officials were suspicious: The winner'due south anonymity was worth $16.v million?

"I was convinced it would never be claimed," says Mary Neubauer, the Iowa Lottery's vice president of external relations, of the jackpot.

And it wasn't, until exactly a yr after the cartoon—less than two hours before the 4 p.m. borderline—when representatives from a Des Moines law firm showed up at lottery headquarters with the winning ticket. The firm was claiming the prize on behalf of a trust whose casher was a corporation in Belize. Its president was Philip Johnston—the same man who said he'd worn a sports coat to buy the ticket.

"It but absolutely stank all over the place," says Terry Rich, master executive of the Iowa Lottery. So they held on to the jackpot while the attorney general's office opened an investigation. Only information technology went nowhere.

2 years subsequently, a infant-faced district chaser named Rob Sand inherited the languishing lottery file. In college, Sand had studied computer coding before going to law schoolhouse, where his specialty was white-collar crime. Still, this case stumped him. His best evidence was that grainy video of a human in a hoodie, then he decided to release the footage to the media, hoping it might spark leads—and information technology did.

The first came from an employee of the Maine Lottery who recognized the distinct voice in the video as that of a man who had conducted a security audit in their offices. A spider web programmer at the Iowa Lottery also recognized the voice: It belonged to a human she had worked alongside for years, Eddie Tipton. Eddie was the information-security director for the Multi-State Lottery Clan, based in Des Moines. Amid the games the association ran: the Hot Lotto.

Eddie cutting a big effigy effectually the lottery office. He wrote software, handled network firewalls, and reviewed security for games in nearly three dozen states. His life revolved effectually his task; he sometimes stayed at his desk until 11 p.m. When a coworker was in a bad mood, one colleague said, Eddie would pat him on the shoulder and say, "I but want you to know I'm your friend."

But he was likewise a paranoid sort. He rarely paid with credit cards, worried almost people tracing his identity. In private moments, Eddie told friends he was lonely and wanted a family unit more than anything. He built a 4,800-foursquare-pes, $540,000 firm in the cornfields south of Des Moines, consummate with five bedrooms and a stadium-style home theater. Friends wondered why a single homo needed such a big house and how he could afford it on his bacon. Eddie told them he had poured his savings into the business firm in hopes of filling information technology with a wife and children. But the right partner never came along.

Amidst Eddie's friends was a colleague named Jason Maher. They spent hours playing the online game Globe of Tanks. When Maher saw the Hot Lotto video that DA Sand released, Maher immediately recognized that familiar, low-pitched voice, but he didn't want to believe it. "That night I saturday down—there's no mode Eddie did this," Maher says.

"In that location's got to be something wrong."

And so he did what a figurer whiz does: He put the file into audio software, removed the white racket, and isolated the voice. So he took footage from security cameras in his ain firm—Eddie had but visited the night before—and compared the voices. "Information technology was a complete and utter match," Maher said. The next mean solar day, he went to the QuikTrip and measured the dimensions of the tiles on the floor, the summit of the shelving units, the altitude between the door and the greenbacks annals. He used the results to compare the hand size, foot size, and top of the man in the video with his friend's. Maher wanted to exist able to tell law enforcement that it wasn't his pal Eddie. "Once I did this, it was similar, 'Well, [expletive]—information technology's Eddie.' "

In January 2015, state investigators showed up at Eddie'due south office. He was arrested and charged with 2 felony counts of fraud. Half a year later, on a hot, sticky July forenoon, Rob Sand stood before a jury at the Polk Canton Courthouse. "This is a archetype story about an inside job," he began. "A human being who by virtue of his employment is not allowed to play the lottery—nor allowed to win—buys a lottery ticket, wins, and passes the ticket along to exist claimed by someone unconnected to him."

The prosecution knew Eddie had bought the winning ticket—the video made that pretty clear. So did cell phone records, which showed Eddie was in town that day, not out of town for the holidays as he had claimed. Investigators believed he'd fixed the lottery. Only if the numbers are supposed to be generated randomly, how did he do it?

Based on his inquiry, Sand theorized that earlier the Hot Lotto jackpot, Eddie had managed to gain access to one of the two computers that select the winning numbers and inserted a thumb drive containing a string of coded instructions he'd written. The surreptitious software, called a rootkit, allowed Eddie to restrict the pool of numbers that could hit—and then information technology deleted itself.

The prosecutor told the jury members that they didn't have to understand the verbal engineering science to convict Eddie. They just had to realize the well-nigh-incommunicable coincidence of the lottery security chief's ownership the winning ticket. Afterwards deliberating for only five hours, the jury found Eddie guilty. He appealed.

Then the example took a very strange plow.

One morning a few months after the original trial, Sand'south office telephone rang. The phone call came from surface area code 281, in Texas, where Eddie grew upwardly. The caller said he'd seen an article in the newsnewspaper about Eddie'southward confidence. "Did y'all know," the tipster asked, "that Eddie's blood brother Tommy Tipton won the lottery, mayhap about x years back?"

Sand contacted Richard Rennison, a special agent at the FBI office in Texas City, Texas. Rennison said he remembered the case well: In 2006, a man named Tom Bargas had contacted local law enforcement with a suspicious story. Bargas endemic 44 fireworks stands. Twice a twelvemonth—after the Fourth of July and New year's day'due south—he handled enormous amounts of cash. A homo he knew, a local justice of the peace, chosen Bargas around New year's day's and said, "I got half a million in cash that I want to swap with your coin."

What'southward a justice of the peace who makes around $35,000 a yr doing with that much cash? Bargas thought. Suspicious, he called the police, who called the FBI. Presently, agents listened in as Bargas met with the justice of the peace, Tommy Tipton. Tommy pulled out a briefcase filled with $450,000 in cash, notwithstanding in Federal Reserve wrappers, and swapped $100,000 of information technology for Bargas's worn, circulated bills. The FBI then went to work investigating the serial numbers on the new bills.

A few months later, Rennison went to see Tommy. He said that he had hit the lottery only was on the outs with his wife and trying to go along the winnings from her. A friend had claimed the $568,990 prize in substitution for 10 percent of the money. At the fourth dimension, it all seemed to add up, and the Tommy Tipton case was closed.

Now Sand suspected that there were even more illicitly claimed tickets out there. He knew from feel that white-neckband criminals aren't usually defenseless on their offset attempt.

In fact, a $783,257.72 jackpot from a Wisconsin Lottery cartoon on December 29, 2007, had been claimed past a Texas man named Robert Rhodes—Eddie Tipton's best friend. On Nov 23, 2011, Kyle Conn from Hemphill, Texas, won $644,478 in the Oklahoma Lottery. Sand saw that Tommy Tipton had iii Facebook friends named Conn. He got a list of possible phone numbers and cantankerous-referenced them with Tommy's cell phone records. Some other hitting.

Two winning Kansas Lottery tickets with $15,402 payouts were purchased on December 23, 2010—the day Eddie bought the Iowa ticket. Jail cell phone records indicated he was driving through Kansas on the manner to Texas for the holidays. One of the winning tickets was claimed by a Texan named Christopher McCoulskey; the other, past an Iowan named Amy Warrick. Each was a friend of Eddie's. Don't miss these 13 things lottery winners won't tell you.

1 forenoon, Sand and an investigator knocked on Warrick'due south door. She told them Eddie had said he wasn't able to merits a winning lottery ticket because of his job. If she could claim it, he'd said, she could proceed a portion as a gift for her contempo engagement.

"You take these honest dupes," Sand says. "All these people are being offered thousands of dollars for doing something that'south a footling bit sneaky but not illegal." Investigators in Iowa now had vi tickets they figured were part of a bigger scam. But the question remained: How did it work?

Fortunately, the computers used in the 2007 Wisconsin Lottery jackpot were sitting in storage. A estimator good, Sean McLinden, unearthed some malicious computer lawmaking. It hadn't been hidden; y'all just needed to know what to look for.

"This," says Wisconsin banana attorney general David Maas, "was finding the smoking gun."

Eddie Tipton pleaded guilty, as did his brother, Tommy. Now facing ten years in prison, Eddie agreed to spill his secrets, which lottery officials hoped would help them safeguard the games in the future. He explained that the whole scheme had started adequately innocently one day when he walked past ane of the accountants at the Multi-State Lottery Clan.

"Hey, did you put your underground numbers in there?" the auditor teased Eddie.

"What do you hateful?"

"Well, you know, you can set numbers on any given solar day since you wrote the software."

"Merely like a little seed that was planted," Eddie said. "So during one slow period, I tried it."

To ensure that the winning numbers were generated randomly, the computer took a reading from a Geiger counter that measured radiation in the surrounding air. The radiations reading was plugged into an algorithm to come up with the winning lottery numbers.

Eddie's scheme was to limit the random selection process as much as possible. His code kicked in only if the coming drawing fulfilled a narrow set of circumstances. It had to be on a Wednesday or a Saturday evening, and one of 3 dates in a not–jump year: the 147th 24-hour interval of the year, the 327th solar day, or the 363rd day. Investigators noticed those dates generally fell effectually holidays—Memorial Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas—when Eddie was frequently on vacation.

If those criteria were satisfied, the random-number generator was diverted to a dissimilar rails that didn't use the Geiger counter reading. Instead, the algorithm ran with a predetermined number, which restricted the pool of potential winning numbers to a much smaller, anticipated set of options: Rather than millions of possible winning combinations, at that place would exist only a few hundred.

The night before the start lottery he rigged, a $4.viii meg jackpot in Colorado, Eddie stayed late in his messy, computer-filled office. He prepare a test figurer to run the plan over and over again and wrote down all the potential winning numbers on a yellow legal pad.

The next day, November 23, 2005, he handed the pad to his brother, who was headed to Colorado on a trip. "These numbers have a good adventure of winning based on my assay," he said. "Play them. Play them all."

On a clear summertime twenty-four hours in Des Moines last year, Eddie Tipton, who was then 54, trudged upwards the stairs of the Polk County Courthouse. His hands were shoved in his pockets, his head down. He had accepted a plea deal for masterminding the massive lottery scam—i count of ongoing criminal deport, part of a package bargain that gave his brother only 75 days. Eddie was hither for his sentencing.

In statements to prosecutors, he painted himself every bit a kind of coding Robin Hood, stealing from the lottery and helping people in need: his blood brother, who had five daughters; his friend who'd merely gotten engaged. "I didn't really demand the money," Eddie said. The judge noted that Eddie seemed to rationalize his actions—that he didn't remember it was necessarily illegal, simply taking reward of a hole in the system, sort of similar counting cards at a casino.

The judge sentenced Eddie to a maximum of 25 years in prison. The brothers' restitution to the various state lotteries came to $2.2 one thousand thousand, even though, co-ordinate to his chaser, Eddie himself pocketed only effectually $350,000.

Sand expects Eddie to exist released on parole within seven years. Reflecting on the case, the prosecutor says he felt a deep intellectual satisfaction in solving the puzzle: "The justice system at its all-time is really about a search for truth." Side by side, read about 15 more than of the unluckiest criminals ever.

abrahamshookeplise79.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.rd.com/article/man-rigged-lottery-five-times/

0 Response to "Guy Buys a Lottery Ticket and Shows How We What Do You Want and How We Wanted and Then Wins Again"

Post a Comment